SEPTEMBER 2020

Shifting Tides: Convergence in Cloth | SAQA Juried Exhibition

In an arc along the western shores of North America to the archipelago of Hawaiian Islands, the Pacific Ocean is a source of life and livelihood. Yet threats to the Pacific ecosystem are growing. These perils challenge our perception of the ocean as limitless bounty. Overfishing and global warming threaten not just oceanic life, but the human communities that depend on it. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch draws in waste material from across the ocean, including coastal waters of Canada and the United States. The ocean knows no boundary. The convergence of these ecosystem issues requires communities and governments to also converge in finding solutions.

Shifting Tides: Convergence in Cloth focuses on the current state of the Pacific Ocean ecosystem, its marvelous natural diversity, and the human activities that both sustain and threaten oceanic life. Whether one lives on the ocean or in the interior, the Pacific touches many lives and economies. As residents of this greater North Pacific region, artists share personal narratives and statements about what exists, current threats, and needed actions. The exhibit includes a representative range of North Pacific mainland and island habitats and issues. The selected works may focus solely on one area of flora, fauna, geology, oceanography and human activity, or may combine them. Subject matter may be inspired by sources as personal as vacations or fact-based as current scientific research. Through the variety of artistic styles and viewpoints from realism to abstraction, Shifting Tides: Convergence in Cloth will delight and challenge viewers to assess their own perceptions regarding the interplay of oceanic and human communities.

Shifting Tides: Convergence in Cloth features the artwork of members of the Studio Art Quilt Associates, Inc. (SAQA). SAQA was founded in 1989 as a non-profit organization whose mission is to promote the art quilt through education, exhibitions, professional development, documentation, and publications. Visit the SAQA website to find out more about the organization.

The exhibition is juried by textile artist Ann Johnston. Find out more about this artist at her website.

Audio Presentations

To hear each artist speak about her artwork, call (703) 520-6404 and enter the Cell Guide number followed by the # sign on your phone.

You can begin by listening to an introduction to the exhibition by Denise Oyama Miller: Guide by Cell #: 2171. Then find a Guide by Cell number for each work below.

Clare Attwell

Surging Tides of Consequences, 2018

Acrylic inks & paints, wheat paste, polyester sheers, photo print on cotton, cotton fabric, polyester batting, thread

55 1/2 x 39 1/2 inches

Cell Guide #: 2172

When Milton Friedman used Leonard Read's essay, "I, Pencil" to illustrate the wonders of 'the invisible hand of the market' in a lecture on free market economics, it captured the imagination of the Western world. The yellow pencil became a symbol of this 'miracle'. One thing Friedman's economics didn't capture was everything that didn't fit neatly onto a spreadsheet – thus, if it wasn't captured on the spreadsheet, it wasn't given value in the new economics. The social and environmental consequences of this approach are now everywhere, from climate chaos to mass human migration and species extinctions. Like the emotional impact of Hokusai's wood cut print, The Great Wave Off Kanagawa, there is a growing sense that life on earth is on an ominous precipice, driven headlong into the violent storm by an economic system incapable of valuing what really matters.

Karen Balos

Port of Oakland, 2017

Paint, cotton fabric, commercial felt, thread

33 x 40 inches

Cell Guide #: 2173

The Port of Oakland links the West Coast to the Pacific Ocean. As an economic entity, it has both the problems (pollution, dredging spoils) and benefits (carbon-saving 'green' routes, i.e. train to ship; ferry commuting service), of that connection. It is our portal to the world, and our responsibility to ecology of the sea.

Photo credit: Sibila Savage

Nancy Bardach

Rising Tides, 2018

Cotton prints, marbelled, and hand painted fabrics, 80/20 batting, cotton texturing threads

60 x 38 inches

Cell Guide #: 2174

Rising seas caused by climate change are threatening to all. Whether urban seawalls collapse or beaches for sea lions and elephant seals erode, human beings suffer and lose. We seem to be surfing uphill in our current battle to avert this tragic future.

Diana Bartelings

Help Me!, 2018

Hand dyed cotton fabric, commercial cotton fabric, netting, plastic and a bead

24 x 37 inches

Cell Guide #: 2175

A turtle tangled in a seining net spies a diver and swims for help. Thankfully the divers are all to happy to help these poor creatures whose ocean has become polluted by our carelessness.

Alice Beasley

In My Wake, 2018

Silks and cottons (both commercial and printed by artist), organzas (silk and polyester); felt backing

56 1/2 x 37 1/2 inches

Cell Guide #: 2176

We all know our oceans are "drowning" in our packaging. But this exhibition has forced me to recognize that ocean pollution isn't just "somebody else's problem", it's my problem too. Each item shown is a fabric replica of packaging culprits that I found in my own house -- the plastic, cardboard, glass, aluminum and paper containers that will eventually have to be disposed of somewhere. (A recycling center? A landfill? An ocean?) This piece shows a worst case scenario: my household disposables adrift in an ocean in the wake of a container ship bringing still more rubbish to me.

Photo credit: Sibila Savage Photography

Beth Blankenship

Nowhere To Run To, Nowhere To Hide, 2018

Polyester and rayon thread, water-soluble stabilizer, commercial fabric, fusible interfacing and glass beads

48 x 27 inches

Cell Guide #: 2177

The Pacific Ocean is warming. This reality spells trouble for many sea creatures, especially those living in frigid northern waters. Cod, pollock and northern shrimp—seafoods we enjoy eating—rely on very cold water to feed and to breed. The range where they thrive is shifting further and further northward. Soon they will run out of "north"—Arctic Cod already have.

Bonnie M. Bucknam

Estuary–Anaheim Back Bay, 2014

Cotton hand-dyes by the artist

60 x 30 inches

Cell Guide #: 2178

I grew up in Southern California where oil production sometimes blended into the environment. The estuary was a place where shorebirds flourished among the oil derricks.

Photo credit: Mark Frey

Sharon Carvalho

Colors of Melting Glaciers, 2018

Materials involve variety of both commercial and personally designed and printed fabrics as well as rice paper. Cottons, sateen, linen, and muslin were used.

41 x 32 inches

Cell Guide #: 2179

"Colors of Melting Glaciers" is second in a series of works providing a visual narrative to accelerating environmental damage.

Glaciers are 10 percent of all land area and are melting at a rate that makes them critical signs for climate change. For example, glaciers in the Cascades have shrunk by about 50 percent since 1900. Worse yet, as global glacial melt continues, sea level rise could reach 230 feet. The chilled waters from glacial melt will do nothing to mitigate warming ocean water. That means not only more frequent and severe hurricanes but also decimation of marine life, including coral reefs—all of which will result in limiting major food supplies for the world.

Photo credit: Melinda Knapp

Barbara Confer

Requiem, 2018

Cotton, chenille, lace, yarn and trims

25 x 36 inches

Cell Guide #: 2180

On the North Coast many old oak trees have become victims of a disease known as Sudden Oak Death, a sickness brought in to the state on plants from South America. Hundreds of old oaks have perished from this disease.

The tree pictured here lived in the large regional park behind my house. Even when no longer alive it is still beautiful.

Judith Content

Sea Change, 2018

Thai silk, various threads, organic cotton batting and raw silk lining

54 x 22 inches

Cell Guide #: 2181

A sea change isn't a modest change, but something that no longer resembles what it once was. If rising temperatures continue and increasingly massive Pacific storms result, coastal ecosystems could experience a perilous metamorphosis. As I worked on this quilt, images of storm surges and flooding swept through my mind and onto the cloth I was dyeing and quilting. "Sea Change" was inspired by an ocean on the brink of radical change.

Photo credit: James Dewrance

Phyllis A. Cullen

The Burning Sea, 2018

Cotton fabrics, hand dyed and commercial, cotton batting, wool roving, cheesecloth, silk and rayon threads, misty fuse, tulle

33 x 38 inches

Cell Guide #: 2182

A photo I took from a boat 10 feet from the lava rushing into the sea was my inspiration to depict the tumultuous events defining our island. The water around us was steaming, and lava bombs were flying.

Caryl Bryer Fallert-Gentry

Splash, 2018

Paint, ink, 100% cotton fabric, acrylic & polyester thread, 100% wool blanket as batting

41 x 41 inches

Cell Guide #: 2183

In June of 2018 we took a photographic expedition to the north end of Vancouver Island in British Columbia. We spent two twelve-hour days on a small boat viewing wildlife. In the Broughton Islands we encountered a pod of 200-200 Pacific white-sided dolphins. They followed in the wake of the boat, jumping through the wake and splashing back into the water, looking like they were having lots of fun. My husband Ron was shooting ten frames per second with a fast shutter speed and caught several pictures of the frolicking dolphins. With Ron's permission, this quilt is based on the most graphic of those photos.

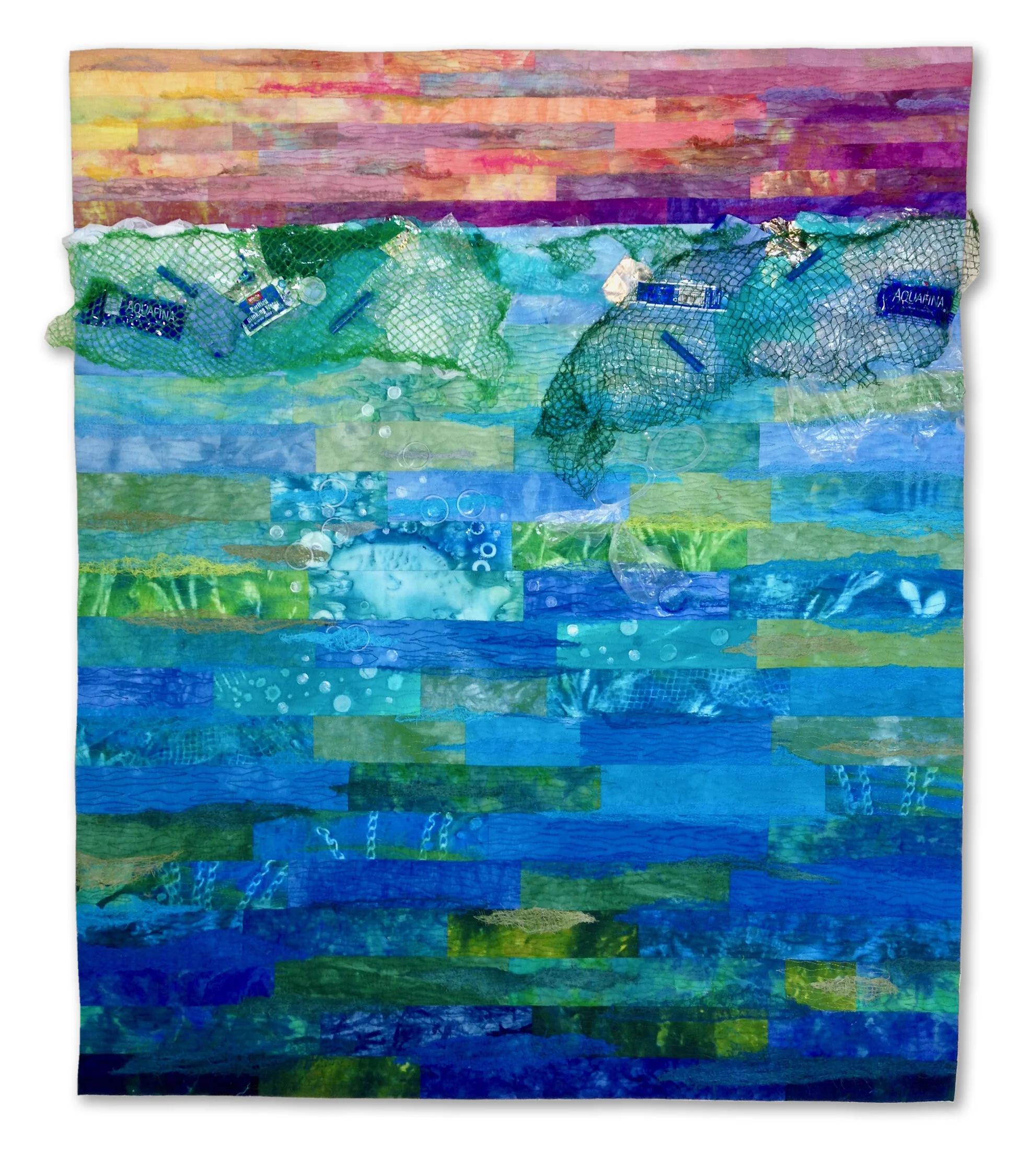

Judith Quinn Garnett

2050, 2018

Over 150 shopping bags, my daily newspaper bags, plastic netting from a neighborhood garage sale, a discarded plastic party table cloth from the recycle center, 100% ECO recycled polyester felt, a repurposed cotton bed sheet

50 x 41 inches

Cell Guide #: 2184

2018 began with the daunting reality that China would no longer accept plastic recycling from the US due to the comingled abundance of contaminated waste.

I was impelled to observe the use of plastics in my own home and began collecting our discarded bags. The pile of seemingly thoughtless waste multiplied as I realized that even our Portland newspapers arrive in plastic bags. As my concern grew, I began fusing the bags as the surface of this piece.

As we ignore this growing mound, research states that by 2050 the plastics that have migrated into the North Pacific will be greater than the population of fish. I hope we can shift the tides of consumption before we drown in the plastic ocean we created.

Photo credit: Sam Garnett

Alisa Golden

Undersea Colonies, 2018

Cotton, silk, linen thread, metallic paint, oil-based ink, black tea, dye, printed cotton

60 x 43 1/2 inches

Cell Guide #: 2185

Vivid colors in a newspaper article opened a world previously unknown to me. Deep in the Pacific Ocean, where plates collide below the cold, earth's kitchen builds lava chimneys, black smokers, and a hot hearth at the Juan de Fuca ridge. Here, tube worms, palm worms, and deep-sea creatures co-exist as they did long before us and will, if we let them, live long after. Already elsewhere, people have disregarded similar life and packed probing tools, intent on dredging for minerals, claiming magnesium, cobalt, and gold for their own. While humans are just dots on a timeline, we still have the choice to impact or respect our collective home.

The fragmented text shifts and collides as follows:

We will not

be planting

a flag on

Juan de Fuca ridge.

The plates rattled

before dinosaurs.

The volcano will spew

after robots.

Tick tock.

Tectonic.

Louise Hall

Atomic Atoll, 2018

Hand dyed and commercial cotton fabrics, batting, thread, and fusible interfacing

36 x 36 inches

Cell Guide #: 2186

The Dome on Runit Island is a legacy of the United States atomic testing from 1946-1958. Runit is one of 40 islands in the Enewetak Atoll, part of the Marshall Islands. Runit Dome, or The Tomb as the locals call it, is a legacy of the 43 nuclear tests the United States conducted there. The 18" thick concrete dome was constructed in 1979 in one of the old bomb craters. The crater, unlined due to cost considerations, is filled with nuclear waste and solid chunks of highly toxic plutonium. The sea level has risen and is penetrating the dome due to the porous nature of the sand and coral that comprises the atoll. With climate change, the increasing ferocity of storms is of enormous concern because Runit is only 2' above sea level. The contents of the dome, as well the surrounding sediments, are dangerously radioactive.

Photo credit: Rhames Photography

Janet Hiller

An Instance of Change, 2011

Hand dyed and over-dyed cotton and cotton/bamboo blends

35 x 40 inches

Cell Guide #: 2187

Every evening is the same--as regular and peaceful as clockwork. Yet every evening presents a different drama in that one instant before the setting of the sun. A shift in light, perhaps. Or the sudden, alarming change in direction of a flock of seabirds.

Photo credit: Jon Christopher Meyers

June Jaeger

Topical Metamorphism, 2018

Both the blue background and the tan map are Kona Cotton solid fabrics. I used Dream Cotton batting and a cotton print fabric for the backing. For hand stitching I used Valdani Pearl Cotton thread, and for machine topstitching I used Aurifil thread.

46 x 36 inches

Cell Guide #: 2188

The Northwest contains a great diversity of climate and landscape including desert, mountains, forests, rivers and ocean side. Our Pacific Ocean maintains our planet's equilibrium, playing the major role of our climate. Thousands of species of birds, fish, and mammals inhabit the Northwest. The mixed ecosystem of sea and land are essential to life. The sediments deposited into the ocean from our rivers help to curb the ocean erosion, creating breakwater, thus protecting the shoreline. "Topical Metamorphosis" portrays a topical map section of the northwest shoreline where rivers meet the ocean, constantly changing...a metamorphosis continues.

Photo credit: Paige Vitek

Lisa Jenni

Rings of Eternity, 2018

Hand dyed and commercial cottons, cotton batiks, quilting threads, Setacolor® textile & puff paint, TSUKINEKO® ink, genuine American recycled fishing net, plastic rings from food and beverage packaging, recycled string

33 x 41 inches

Cell Guide #: 2189

A gigantic collection of plastic, trash and lost fishing nets is floating halfway between Hawaiʻi and California. Its size is said to extend over an area bigger than the State of Texas. However, this floating mess is not unique to the northern Pacific, a similar patch of debris is found in the Southern Pacific, North & South Atlantic Ocean and the Indian Ocean.

Much of the plastic trash, such as the little safety-seal rings on food and beverage containers, could be avoided, if consumers, producers and waste managements worldwide would work together to find better alternatives. Especially these colorful rings have been found in carcasses of chicks of albatrosses, who die eventually of malnutrition.

Jennifer Hammond Landau

Mighty Mussel, 2018

Wool fleece, tulle, silk, and synthetic sheer fabric

34 x 38 inches

Cell Guide #: 2190

Mussels thrive along the Pacific coast, providing a critical role in the ecosystem as well as a tasty meal. Like other bivalves, mussels are a natural filtration system, cleaning toxins from tidewaters. In using mussels to test the pollution levels in Seattle's waters, disturbingly, scientists are finding high levels of caffeine and opioids. I admit that this "household cleaning" function makes me wonder a bit about what I am ingesting when enjoying the family favorite, "Moules Frites.

Photo credit: Sibila Savage Photography

Cat Larrea

Tidewater Glacier, 2018

100% cotton, cotton thread, eco-fi felt batting

30 x 36 inches

Cell Guide #: 2191

A tidewater glacier is one that reaches the sea. Having lived for over thirty years in Alaska, one of the most dramatic indicators of global warming I have witnessed is the alteration and thermal erosion of our sea level "ice rivers". My representation simplifies how multiple glaciers, like rivers, can flow together. However, in a relatively short time, my imaginary glacier will become two independent ones as it melts and seemingly withdraws up each valley. Gone will be its icebergs, its thunder as it fractures and calves, and in its place will be new exposed earth, ready for the change vegetation brings.

Sherly LeBlanc

Pacifica, 2018

Commercial and hand dyed fabrics, yarns, sequins and beads

59 x 41 inches

Cell Guide #: 2192

The vessel "Pacifica" symbolizes the rapidly diminishing livelihood of the single commercial fisherman. With the deleterious effects of rising water temperature, pesticide runoff, radiation mutation from Fukishima, oil spills, and continued silting of the ports and harbors, not to mention historical over-fishing, the future of this way of life is bleak.

Photo credit: Jon Christopher-Meyers

Nancy Lemke

Seaside 2, 2018

Commercial fabrics, acrylic paint, antique crocheted doily, beads

27 x 42 inches

Cell Guide #: 2193

When I was little, my family vacationed on the beaches of Oregon and Washington each summer. We walked for miles along the deserted sand, dug clams, and at low tide, we'd visit the odd creatures that live in tide pools. Sometimes my dad fished for salmon. Something about the beach dissipated my mother's chronic depression, and we all basked in the warmth of her happiness. Despite growing development, Pacific beaches remain magical places for me, reminding me of the times when I could reach out for my mother and she would be there for me.

Photo credit: Gary Conaugton

Jacqueline Manley

Widening Gyre of Flotsam, 2018

Monk's cloth, satin, Czech crystal beads

26 1/2 x 39 inches

Cell Guide #: 2194

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is a manifestation of harmful human practices on the Earth, perhaps more explicitly visible than overall climate change. Located between California and Hawaii and twice the size of Texas, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch formed within an ocean gyre of circular currents. Contents are estimated to weigh at least 80,000 tons and contain 180 TRILLION pieces of plastic—250 for each person in the world! Various plans are being created for cleaning up the garbage; none are quick fixes, and all emphasize reducing the use of plastics and the improvement of recycling efforts.

Kathleen McCabe

A Quiet Moment, 2018

Commercial and hand painted cotton, batting, and thread

28 x 42 inches

Cell Guide #: 2195

The sound of waves crashing, the smell of fresh, salty air, the calm of the vast horizon; all these sustain us in an otherwise chaotic world.

Photo credit: Phil Imming

Amanda Miller

Jumping the Gorge, 2017

Commercial cottons and silk

42 x 30 inches

Cell Guide #: 2196

Summer is fire season in the Pacific Northwest, but in recent years, annual wildfires have taken on more intense and frightening aspects. Smoke chokes communities for weeks, Homes are destroyed while people and animals flee the blazes. Last summer fire even jumped the Columbia Gorge to continue burning on the far side. There is not complete agreement or a singe solution for mitigating the damage of these fires. Increased educational efforts along with restrictions on fireworks and campfires during dry seasons could decrease human-caused blazes. Changes in forest policies could restrict the size of the fires. More careful land use planning and restrictions on developing high risk areas should also be considered.

Photo credit: Jon Meyers Photography

Denise Oyama Miller

Pelagic Produce, 2018

Commercial and hand-dyed cotton fabric, fleece, fusible

59 x 24 inches

Cell Guide #: 2197

The kelp forests are recognized as one of the most important and productive ecosystems in the world, providing shelter for fish and other animals and protecting the coastline from potentially destructive storms. In addition, they are a nutrient dense food that is low in fat/calories, high in iodine/calcium/vitamins, and that strengthens your immunity. Kelp are used to not only make the wrappers for sushi rolls, but are also included in products from toothpaste to ice cream. We need to continue to look towards the ocean to help provide healthy food for the world's population and to protect that ecosystem from destruction and pollution.

Photo credit: Sibila Savage

Cathy Miranker

Whither the Waterfront?, 2018

Commercially available polyester wall tapestries, 12 wt variegated threads, 30 wt cotton and polyester threads

57 x 41 inches

Cell Guide #: 2198

With sea level rise already remaking shorelines and cities worldwide, this quilt offers a deliberately alarmist vision of what might happen to San Francisco's iconic downtown. It deconstructs images of real buildings that hug the water's edge and reconstructs them … in different places, akilter, even partially submerged. Machine embroidery hints at an additional, ever-present threat: seismic upheaval.

Photo credit: Douglas Sandberg

Deborah Runnels

Promise of the Pinecone, 2018

Hand dyed and commercial printed cotton

46 x 32 inches

Cell Guide #: 2199

The pine cone has been an inspiration to cultures throughout history. Dionysus carried a staff with a carved pine cone symbol on its' tip. So does the papal staff of the pope. To the Celts, it was a fertility symbol and our own human pinal gland looks like a pine cone (hence the name) and is the epicenter of our enlightenment.

There is hope that evolves naturally after the presence of fire. We can look to the pine cone as our symbol for the promise of new growth.

Nancy Ryan

Water, 2018

Cotton fabric, acrylic paint and specialty threads were used to create this piece

25 1/2 x 36 1/2 inches

Cell Guide #: 2200

Not all trash ends up at the dumps. The great Pacific Garbage patch stretches across a swath of the North Pacific Ocean forming a nebulous, floating junk yard on the high seas.

Plastic that begin in human hands yet ends up in the ocean endangering our marine life. It is time to shift tides and we humans need to protect instead of polluting our waters.

Roxanne Schwartz

Agua Caliente, 2018

Hand-dyed and commercial cottons, wool batting, poly and cotton threads

60 x 29 inches

Cell Guide #: 2201

Heat ripples through our Pacific Ocean as her currents undulate to sister oceans across the planet. Sinuous stitching lines and fluid shapes suggest streaming, bubbling movement. Color suggests both coolness and warmth, and perhaps a disturbing muddiness. A bright line breaks the flowing shapes, radiating change. Our oceans are connected but troubled. Since 1880, ocean temperatures have been tracked; they show a warming trend, with some dips in the mid-twentieth century. But no dips have been recorded since 1985. Warmer oceans now surge through the planet, affecting sea life, food security, weather, coastal habitats throughout the world. What is our next step?

Photo credit: Dana Davis

Janet Scruggs

Plastic Chowder?, 2018

Various fabric types including cotton, recycled unknown fibre, cheesecloth, and flannel. Felt, polyester and rayon thread, and beads.

24 x 22 inches

Cell Guide #: 2202

The issue of plastics causing harm to marine life and birds in our oceans has been widely publicized. But did you know you could be ingesting micro-plastics when you enjoy that bowl of clam chowder, steamed mussels or oysters? Researchers at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia have found that many shellfish farms are polluted by micro plastics. These can come from plastic that is breaking down (fibres from clothing, carpets and other textiles), plastics used in the industry itself, or microbeads that are used in personal care products. These micro-plastics are being ingested by shellfish and then we in turn consume them in clams and other shellfish. This growing concern inspired me to create a collage reflecting the breaking down of the plastic and how microbeads are becoming part of the clam food chain.

Maria Shell

Break Up, 2018

Vintage, contemporary, and hand dyed fabrics, batting, thread

40 x 30 inches

Cell Guide #: 2203

Northerners have special names for the mucky weather of spring. In Alaska, we call this time of the year Break Up. Snow from the mountains begins to melt and dirt roads become creeks. Ice rots and mud rules. The change is so slow that we all grow impatient wanting the light, the sun, the dry land. I love this season. Everyone's yard looks like a junkyard. There is no snow or leaves to hid your business. You spend your days adding and subtracting layers of clothing, and the sunlight just keeps coming. It is a restless naked season I think.

Photo credit: Chris Arend

Sue Siefkin

Blue Reverie in Peril, 2018

Acrylic paint on habotai silk; hand-dyed cotton; glass beads

41 x 31 inches

Cell Guide #: 2204

The deep, mesmerizing blues of our oceans are relentlessly threatened by the impact of global warming and thoughtless human activity.

Sigrid Simonds

Oil On The Beach, 2018

Cotton, embroidery floss, dye, wool batting and cotton thread

38 x 25 inches

Cell Guide #: 2205

While vacationing on California's central coast and walking on the beach in early mornings the patterns left on the sand by the ebbing water caught my eye. The patterns were dark lines. After a little research I discovered the dark lines are tar ground fine from natural oil leaks or manmade oil spills. This piece is my abstract version of these lines. These are the colors of the sand and oil and the red is my interpretation of warning, the oil should not be there.

Gail P. Sims

Spiraling Out of Control, 2018

Cotton, evalon, silk ribbon and King Tut thread

30 x 23 inches

Cell Guide #: 2206

California and the entire North West US and Canada have been greatly affected by horrendous fires in the last few years. Since the recent fires are more and more reaching into urban areas, the toxic pollutants will cause dangers on both land and sea.

This piece was inspired by the recent Santa Rosa, Redding and Paradise fires with smoke and air quality the like of which we have never seen before. The wind patterns pushed extremely hazardous air quality into the San Francisco bay and inland to the central valley. Although I was just an hour away, the worst quality was over three hours away. Total damage is not yet known in the most recent fire because the blessing of rain has its own issues.

Photo credit: John Sims

Bonnie J. Smith

Moss Beach, 2016

Hand dyed silk & cotton fabrics; Kona Cottons, Cotton Polyester batting, cotton and polyester threads

43 x 39 inches

Cell Guide #: 2207

So many times in my life I have visited Moss Beach that is situated on the Pacific Ocean in Northern California. With each visit I make my way around the worn foot trail, walk up the incline to view this piece of nature's wonderment and I am never let down. But, lately in the last few years it is different, the waves have gotten so wild and almost mean that rock boulders have been pulled away and I cannot see that most prefect view that I used to take for granted

I fear climate change and what humans have literally dumped into the ocean has caused the Pacific Ocean to rear its head and say "no more", I will teach you a lesson my way.

Photo credit: Spring Mountain Gallery

Amanda Snavely

Life in Abstraction, 2018

Silk Organza, Cotton, Wool Interlining, Metallic thread, Silk thread, Cotton Thread, Acrylic Paint

48 x 33 inches

Cell Guide #: 2208

Wandering along the water's edge, one glimpses the magical world beyond the hazy veil of salt spray. Encrusted on the rocks are gooseneck and acorn barnacles, limpets, anemone, and mussels packed tightly together. These intricately patterned creatures face environmental damage-the crashing surf, the drying sun, harvesting as delicacies, and damage from humans in their quest to view this delicate ecosystem. The barnacles chatter as they move inside their shells reminding us to observe without disturbing. The organisms arrange themselves so closely together that the creatures visually merge: the eye cannot distinguish where one creature ends and the next begins. An abstract pattern emerges as the contrasting shapes compete for space in one small crevice. Delicate beauty such as this reminds us we must look with our eyes instead of our hands to preserve this natural art form.

Photo credit: Sam Garnett

Carla Stehr

Diatom 8, 2015

Ecofelt, three layers of hand dyed cotton fabric. Fabric paint.

28 x 33 inches

Inspired by a scanning electron microscope image I photographed during my career as a Marine Biologist.

Cell Guide #: 2209

Diatoms are tiny, single-celled aquatic plants. A microscope reveals they have complex multilayered cell walls with stunning patterns. A liter of sea water may contain up to a million of these microscopic algae. Diatoms generate about 25 percent of our oxygen and absorb 30 percent of earth's carbon dioxide. Water temperature and nutrients influence diatom growth, but this complicated balance is also affected by climate change and ocean acidification. Some (including toxic species) are becoming more prevalent while other species are declining or moving to colder waters. These changes may affect the future ability of the ocean to sequester excess carbon dioxide. Fish, bird and mammal populations may also change because they depend on the diatom-based food chain. The microscopic beauty of diatoms is a reminder that even the tiniest organisms are incredibly important for life on earth.

Nan Thompson

Copper River Flats, 2018

Hand-dyed and commercial cottons

46 x 37 inches

Cell Guide #: 2210

This is an image of the Copper River Delta in Western Alaska where my husband works as a commercial salmon fisherman. The changes in ocean temperature have affected the Alaskan wild salmon runs. The Chinook (a/k/a King) species is the largest; commonly weighing over 30 pounds. They are born in freshwater streams and live three to eight years in the ocean before they return to their freshwater river birthplaces to spawn. Commercial fishers harvest them on the river deltas like the one in this image, where the fish leave the ocean and begin traveling upriver. Over the last thirty years, Chinooks have gotten smaller in all of the ten rivers studied by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. That agency has restricted the allowable catch for commercial and sport fishers and people who live along the river who depend on salmon as a food source.

Photo credit: Kwangsook Schaefermeyer

B. Lynn Tubbe

Pacific Garbage Patch(work), 2018

Sun printed and hand dyed fabrics, hand dyed cheesecloth, commercial fabrics, fabric paint, cotton and polyester threads, cotton batting, upcycled items of plastic less than .5 inches deep

41 x 35 inches

Cell Guide #: 2211

This piece reflects my concern for our Pacific Ocean, and its huge "garbage patch" filled with plastic and trash. 80,000 metric tons floating between Hawaii and California, it has become an ugly monster. The debris abandoned by fishermen and the plastic trash discarded by nations bordering the Pacific are killing wildlife, polluting our ocean, and fouling our beaches. Recently a dead whale was found to have over 1000 pieces of plastic in its stomach. And videos of rescuers cutting creatures free from entangled fishing lines are wrenching to watch.

My little fish, curious about the plastic garbage around it, may suffer the same fate.

By raising our awareness of the dangers of plastic, which does not decompose, I hope solutions can be found for this menace to the Pacific Ocean and, indeed, our entire planet.

Carolyn Villars

Low Tide at LaJolla, 2016

Cotton, procion dyes, Superior threads

43 x 32

Cell Guide #: 2212

A golden evening with the family at the tide pools, watching the sun sink into the Pacific. The long beach was a sheet of shimmering reflections, the children romped with bare feet on the sand, and even the teenager was present, phone in hand.

Deborah Weir

Haida Waters, 2014

Cotton

36 x 24 inches

Cell Guide #: 2213

Water is a daily concern for those who live near the Pacific Ocean. We experience its beauty, its life-giving powers, and its fragility. We also misuse it wantonly; billions of dollars and countless human hours are spent retrieving it and cleansing it. Life and death in one mighty resource.

Haida Waters is the dance of wild salmon programmed to climb unimaginable heights just to spawn.

Jean Wells

SOLVE Works!, 2019

Linen, cotton, silk

42 x 39 inches

Cell Guide #: 2214

Oregonians are blessed with the pristine beaches of the Pacific Ocean. In recent years SOLVE, a voulteneers-based organization has an annual event to clean the beaches of debris left behind by people who recreate on our coastline. This effort has positively impacted our beaches in Oregon. Manzanita is our family's favorite beach. We are pleased the clean up allows us to continue our enjoyment of the seasonal rhythmic movement of the waves as the ocean meets the shore.

Photo credit: Gary Alvis

Libby Williamson

Ripples Untended, 2018

84 used tea bags, hand-painted papers and fabrics, cotton, wool, silk, upholstery fabric, burlap, vintage linens, non-woven fabrics and acrylic paint

60 x 44 inches

Cell Guide #: 2215

Glaciers melt, seas rise, waters warm and chaos ensues. While the absurd debate over climate change persists, consequential damage is hidden beneath the dazzling aquamarine currents, the cresting waves, and the steadfast tides.

Giant kelp forests, harboring complex and balanced ecosystems, struggle to resist the destruction. Their demise triggers a cascade of turmoil, unseen from above.

Amy Witherow

Sandpipers at Ebb Tide, 2018

Cotton cloth, thread, and batting. Tsukeniko inks

30 x 30 inches

Cell Guide #: 2216

At ebb tide, sandpipers forage in a reclaimed salt pond that was once part of the Cargill Salt Ponds—originally covering 16,500 acres in San Francisco Bay. These once-stagnant industrial ponds were returned to tidal wetlands as part of a 30-year project, the South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project. Now, with a healthy flow of water pulsing through these ponds, the area provides habitat for waterbirds and other wildlife. Outdoor enthusiasts enjoy the scenery while walking and biking on trails in an area that once was inhospitable.

Ann Johnston

JUROR’S QUILT

Wave 15, 2017

Whole cloth cotton, monoprinted and hand painted with thickened dye, machine stitched

37 x 35 inches

Cell Guide #: 2217

I have spent a lot of time staring at ocean waves and wondering how to make that sensation into a quilt design, imagining the complex forces that create a wave, imagining what it feels like the color of—among other things—heat and anger. It won’t be long before the many of the changes occurring in our ocean will be irreversible.